When Calvin Ridley was suspended for betting on NFL games in 2022, it was largely dismissed as an isolated incident among the four biggest North American professional leagues in the era of legalized sports gambling.

He served a yearlong suspension, penned a lengthy apology calling it "an isolated lapse in judgement," and was reinstated in March.

But in April when three players were disciplined for betting on NFL games and two more for placing wagers on non-league games, followed this month by an investigation into another player, a spotlight shone not just on the NFL but U.S. sports betting as a whole. While none of the players' actions were related to attempts to fix games, the incidents have driven a public conversation about the integrity of pro sports as legalized sports betting takes a greater hold in this country.

"Leagues are dancing with the devil," said Declan Hill, a professor at the University of New Haven who consults for Interpol and pioneered the first online anti-match-fixing education course. "Here's what happens. There'll be one play that's kind of weird and dubious and sports fans will start to go, 'Was that legitimate?' And then there'll be another one. And another one and another one. And after a few years, the sports leagues will have a problem. Because their fundamental credibility is being debated by their fans."

People are also reading…

The discussion comes at a time when athletes in the U.S. are closer to gambling than ever before.

Images of players are being used in sportsbook advertisements. Sportsbook ads have prominent placement in stadiums and arenas, including some with on-site betting. Major League Baseball — long the most gambling-averse of the U.S. leagues — now permits its players to be ambassadors for gambling companies.

It's the backdrop for legal sports betting in the U.S. that's generating huge revenue, with Americans wagering more than $220 billion during the five years since the Supreme Court cleared the way for states to offer sports betting. The NFL, NBA, MLB and NHL are among the biggest winners, turning official data that is the lifeblood of in-game betting into profits by selling it to technology companies that distribute it to sportsbooks. Leagues have partnered with those same tech companies to help them watch for fraud.

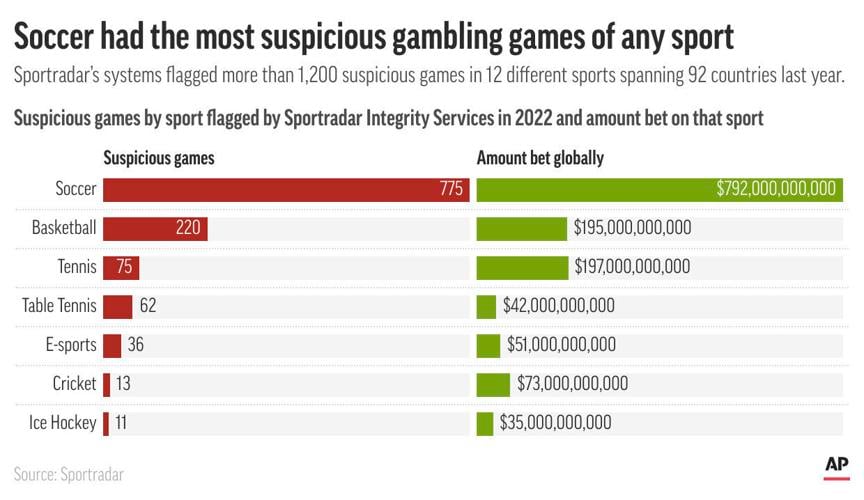

The potential pitfalls of gambling were highlighted by Switzerland-based Sportradar, which has data and monitoring agreements with the NBA, MLB and the NHL. In its second annual report "Betting Corruption and Match-Fixing" released in March, the company said that while data for 2022 gleaned from its Universal Fraud Detection System showed that more than 99% of sporting events are free from betting corruption, it "remains a constant and growing threat across the world of sport."

Sportradar's systems flagged more than 1,200 suspicious games in 12 different sports spanning 92 countries last year. The highest number of suspicious games (775) were in soccer.

Soccer is the most bet on sport globally ($792 billion last year). Among individual leagues, the NFL ($150 million) was behind only UEFA Champions League ($245 million) and English Premier League ($220 million) last year.

Sportradar Integrity Services managing director Andreas Krannich noted fixing efforts are found mostly in lower-tier sports and leagues, but said they are constantly in a race to update tools "to try to catch up or to stay ahead of the criminals."

Though technology companies' monitoring methods vary, there are similarities. All use systems that scan the betting market for irregularities, such as abnormal amounts wagered on events. The companies then alert their clients (leagues and sportsbooks) of possible manipulation.

The NFL has contracted with London-based Genius Sports since 2021. The NBA extended its agreement with Sportradar in 2021. The NHL and MLB also incorporate Sportradar into their protection measures. Genius Sports, StatsPerform and Swish Analytics also have deals to be U.S. distributors of MLB's data.

Most contracts include provisions that allow the tech companies to sell things like odds and real-time stats that can be turned into in-game betting products, but there are exceptions. U.S. Integrity (used by MLB, the NBA and several sportsbooks) is independent and doesn't make betting products for sportsbooks.

"I can see there's an inherent conflict of interest in that we're asking them to help monitor the integrity and they're making money from the sportsbooks," said Kenny Gersh, MLB's executive vice president for media and business development. "That said, they understand the bigger picture and that if there is an integrity issue or a violation at one random sportsbook, it's going to infect and sort of crater their entire business."

A staple of state gambling laws is a requirement for sports betting operators to employ monitors and alert regulators to issues or face fines or license revocation.

But there is nothing that forces the leagues to share with the public the information they receive from monitoring companies.

Experts believe that is a missed opportunity to reassure bettors.

"My biggest issue with the integrity monitoring industry is that they work for the leagues — that's who pays their bills and that's who they work for," said John Holden, an Oklahoma State associate professor who holds a Ph.D. in sports law and corruption of sport. "Their job is not necessarily to work for the public."

In each instance where monitoring is believed to have helped tip off the NFL, the league said no inside information or games were compromised. But NFL spokesman Alex Riethmiller acknowledged companies like Genius Sports "serve an important role in our efforts to protect the integrity of the game."

"Because they are integrated with the vast majority of the betting market, they are well-positioned to help the NFL monitor for unusual activity and report concerns across the industry, enabling critical information-sharing," Riethmiller said.

The Big 4 all have rules prohibiting league employees and players from betting on their own games. But none of the four bar their players from betting on other sports.

The leagues aid the monitoring companies by providing lists of players and other personnel restricted from betting on their respective sports, while putting their players and personnel through annual training.

The ultimate fear is that gambling by players and league personnel could make them susceptible to sharing inside information that could aid match fixers.

That potential was on display in 2015 when cheating allegations rocked the daily fantasy sports industry after a DraftKings employee was accused of using insider knowledge to win $350,000 in a contest offered by competitor FanDuel.

With an online reach that now covers more than 40% of the U.S., FanDuel's online sportsbook general manager Karol Corcoran said safeguarding integrity remains "front and center" for every new state launch it makes.

"We're in an ecosystem with customers, we're the operators, with the leagues, with our data providers," he said. "It's important for all of us that we build together a sustainable industry. And being very careful about integrity is part of that."