EAST HELENA, Mont. — Steve Wagner stepped on the stage and gazed out over the pews. He was at the Canyon Ferry Road Baptist Church to baptize a few dozen believers in a new Christian nationalist movement, one that’s crystalized around the idea that citizen-spurred grand juries and county militias are the instruments against omnipresent government corruption.

The stakes, Wagner told them through a wired microphone headset, could not be higher.

"We know we are sitting ducks. This criminal gang in Washington, D.C., right down through the channels of our state in the temples of government, we know that they could pick any one of us off at any minute, and there’s not a lot we can do about it," Wagner told the audience.

At the meeting that night in April 2021, Wagner marshaled the simmering resentment in the room over public health measures to stem the spread of COVID-19, the 2020 election results and Black Lives Matter riots. He told the few dozen seated before him that these events had primed them all.

People are also reading…

"They can shut our business down; they can drain our bank account. Won’t be long before they have their way. You can't go hardly anywhere unless you've got your little card that says you've been vaccinated — that's what's coming, we all know it, if we stay on the course that we are."

Wagner, who lives in Whitehall, Montana, told the group they were now all on the forefront of turning the tide back, if they were willing to roll up their sleeves and do the work.

"They'll be writing about us in the history books and children will be reading about us as they live lives as free, sovereign Americans, when we do this, if we do it," he said.

This gathering was one of the first official recruiting events in Montana for Tactical Civics, an organization founded in Texas by retired engineer David Zuniga. It teaches disciples that the United States is a Christian nation and that they, the "repentant remnant," are empowered to pursue publicly elected officials they deem have violated the U.S. Constitution.

Tactical Civics claims to have 450 members in Montana, each of whom pay a $5 monthly membership to access the group's literature online, and chapters in nine counties. The organization has found harbor with some state lawmakers and used a statewide ballot initiative campaign earlier this year as a vehicle to recruit across the state.

Montanans who attended that 2021 meeting in East Helena or others in the following months, according to interviews with more than a dozen current and former Tactical Civics members, were worn down by the feeling that they were watching life happen to them. In some cases, they had driven over 100 miles, desperate for something to take hold of.

Tactical Civics offered them an education — an interpretation of history and constitutional law that no one ever taught for them before. Zuniga has written over a dozen books, including titles for homeschooled children and church leaders, telling Americans they are not only active participants in their lives, but the bosses of the lawmakers, governors and judges.

"During the COVID time, we were desperate to find organizations that would be part of the pushback against government overreach," Alan Lackey said.

Lackey is part of another group, Stand Together For Freedom, which similarly seeks to push back against perceived government overreach where it can be fought at the local level. He had driven 150 miles to the meeting that night from Ravalli County, particularly curious about the plan for restoring grand juries as they functioned around the time of the country's founding.

At events across Montana in the last year, Tactical Civics members told potential recruits they could indict corrupt law enforcement officers, judges who have taken away people’s rights or politicians who have failed to act on the immigration crisis.

And when local law enforcement refuses to go along with the grand jury indictments? Well, that’s what the county militia is for.

In total, Tactical Civics has a four-phase plan to redeem the country in its followers' eyes. First, they must assemble county chapters to a membership level that reaches one-half of 1% of the local voting population. Next, those chapters will take ordinances, pre-written by Tactical Civics, to their county commissioners to formally recognize the grand juries and militia.

The third and fourth phases turn Tactical Civics’ attention on Congress: pressing more than 20 states to ratify a measure that would cap representation of congressional districts at 50,000 people. That would effectively create about 6,500 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. The last phase would see Congress pass a law requiring those federal lawmakers work from home in their own districts, theoretically away from power politics and lobbyists' nests in Washington, D.C.

At the East Helena meeting, Jim Abell couldn't believe what he was hearing. Montana, which currently has two congressmen, would get 21. In its current arrangement, Montana holds .46% of the seats in the U.S. House, while under Tactical Civics' plan, Montana’s representation in the U.S. House would fall to .33%.

Math, however, was not what brought Abell to the East Helena church that day. The temperature of the political rhetoric had begun to frighten him, as had the kind of activity then-former president Donald Trump whipped up after his 2020 election loss.

Jim Abell poses for a photo in Helena on Nov. 18.

Going to a meeting like that was rare for Abell, a Helena resident who plays pickleball, keeps up with the happenings in state government and speaks softly about the way the world concerns him. But after seeing political violence jolt the United States on Jan. 6, Abell said he wanted to see the movement up close. He was surprised to find it wasn't Proud Boys or men in military fatigues.

"The church was packed and people looked normal, like me," Abell said.

Tactical Civics instead claims to not be a militia organization; it merely educates citizens on how to form a "constitutional militia" themselves, "one county at a time."

The organization works hard to distance itself from the militia movement, although in Zuniga's militia handbook, "Time to Start Over, America," he describes attempting to meet with, and ultimately being run off by, the Three Percenters, and disrespected at another event by Oath Keepers leader Stewart Rhodes, who for a time lived in Montana.

The Southern Poverty Law Center earlier this year listed Tactical Civics for the first time among the anti-government groups it tracks annually across the United States.

David Zuniga’s militia handbook, “Time to Start Over, America.”

"The citizen grand jury idea goes back to the Posse Comitatus, the (Montana) Freemen, that citizens can assemble grand juries and hand down criminal indictments," said Travis McAdam, a researcher with the Southern Poverty Law Center. "It's about going after their perceived enemies, people who have wronged them."

Not everyone clung to Tactical Civics' plan, while others said they were purged for deviating from the script. Lackey, for example, violated Tactical Civics rules by running for the state Legislature, where he had plans to install some of Tactical Civics' policies in state law. Zuniga, Lackey said, snuffed him out of the organization.

"He got very angry with that and said all politicians are snakes and that’s not the way to do it," Lackey said.

That doesn't mean Tactical Civics hasn't found a footing in Montana politics.

In Gallatin County, one of the fastest-growing areas by population in the country, the local Republican women's committee maintains a Tactical Civics page on their website under "Resources."

"I'm in full support of Tactical Civics and grand juries, because we have a tremendous problem with our courts," Randy Pinocci, a Republican elected member of the Public Service Commission, said on a Great Falls radio show with Tactical Civics' regional coordinator Bart Crabtree in June.

Pinocci did not return a call seeking comment for this story. He generally circulates in the far-right wing of Republican circles, having once held a vigil at the Montana State Capitol for those arrested in the Jan. 6 riots.

Crabtree, of Great Falls, has been on a crusade against the judicial branch since a felony conviction in 2017.

From right, Jordan “J.D.” Hall, Randy Pinocci and Steve Wagner lead a small group of people in prayer during a Jan. 6 remembrance ceremony on Jan. 6, 2022, in the Montana State Capitol Rotunda.

'Temples of government'

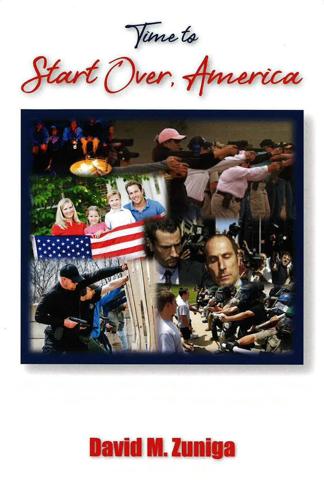

In a first-floor committee room at the state Capitol nearly two years ago, Crabtree explained to lawmakers the function of House Bill 589. Republican Rep. Lola Sheldon-Galloway carried the legislation, but stepped aside so her constituent could better explain.

"Once that grand jury is empaneled, they are the top law dog of the county," Crabtree told the House Judiciary Committee that February. "They are the pinnacle of the law system in that county."

Bart Crabtree testifies in support of House Bill 589, to establish citizen grand jury in Montana state law. Rep. Sheldon-Galloway, R-Great Falls, carried the bill on Crabtree's behalf.

Wagner, by this time, had suffered some health issues and stepped aside from Tactical Civics, and Crabtree became the organization's statewide coordinator. He didn't mention Tactical Civics during his testimony, instead introducing himself through his own organization, Montana Citizens Council on Judicial Accountability. However, Sheldon-Galloway’s email exchanges with legislative staff showed Crabtree raised Tactical Civics blueprints for grand juries during his work in drafting the bill.

"I brought it because it was a group of constituents in my county," Sheldon-Galloway said an October interview in Liberty Hall, an empty Great Falls business space that served as a pick-up location for Republican campaign materials during the election. "It's my job as a legislator to bring those citizen ideas to the session. There's good discussions there, it's a good venue for that. And I support my constituents."

Sheldon-Galloway, a fourth-term state representative, said she would not blindly carry any legislation on her constituents' behalf — certainly not a bill to help ensure abortion access or to water down gun rights, she noted. Tactical Civics had met there in that same building where she was handing out informational pamphlets supporting GOP candidates, she said, adding she never stuck around at those meetings or got involved in the organization.

"What I've seen, they would come in and hold their meetings," she said. "They would open the Constitution and study it. … The people I know who are on Tactical Civics, I don't find them bloodthirsty. But citizens are frustrated and they're looking for answers."

Even before Wagner was warning about corruption in "the temples of government," Crabtree felt the system had wronged him. He was convicted of felony theft — at a jury trial in which he represented himself — that emerged out of a dispute about the finances of a girls' softball organization in Great Falls.

Bart Crabtree testifies as an expert on judicial standards before the Law and Justice Interim Committee on May 9, 2022.

Crabtree maintained his innocence in that case, contending that witnesses had lied, the police had committed fraud and, above all, the judge had shown bias against him. That case was the "catalyst," Crabtree said, to start up his own organization, Montana Citizens Council on Judicial Accountability. The organization's website lists his own case under the title, "Corrupt Conviction."

"That's why I started it," he said in a July interview. "Because I know there are other people out there who have been screwed by the system."

He became known around the Montana State Capitol in 2021 for his efforts to create citizen oversight over the judicial branch through bill to give citizens a wide majority on the Judicial Standards Commission, which has the power to remove sitting judges. That and a small handful of other bills that session turned out to be another catalyst, setting off a separation-of-powers dispute between the GOP-controlled Legislature and executive branches against the courts.

In brief, Republicans soon learned judges, discussing legislation in internal emails, had branded the Crabtree bill and a few others as unconstitutional. Those emails were rocket fuel for Republicans, whose policy ambitions have become routinely subject to legal challenges.

As lawmakers considered options to gain an upper hand, Crabtree remained a fixture of the Capitol gallery and public comment periods. At one point he was called upon to give a presentation to lawmakers on judicial standards.

In the background, Crabtree continued fighting his conviction. He lost his appeal; his petition for post-conviction relief accusing the judge of bias and the police of fraud was denied; the complaint he submitted against the judge in his case was rejected.

In one decision, Montana Supreme Court noted Crabtree's legal arguments had amounted to "casting other witnesses, law enforcement detectives, prosecutors and the district court judge as conspirators in a grand scheme of lies against him."

Crabtree has since completed his sentence for the theft, and didn't flinch when asked in July whether he regretted representing himself in court.

"I'm glad how things turned out, because we're exposing what's going on," he said. "That's — I don't know — my calling."

Ultimately, the two bills Sheldon-Galloway carried on Crabtree's behalf died in committee. Crabtree said he was shocked; Sheldon-Galloway carries more sway than a common legislator, she's the vice chair of the Montana Republican Party.

Rep. Lola Sheldon-Galloway, R-Great Falls, on the House floor of the state Capitol on March 1, 2023.

"It's just odd," he said. "We had a lot of support behind it, and it just gets blown out of the water."

Undeterred, Crabtree moved forward with the next chance to put grand jury reform into place, driving ahead with a statewide ballot initiative campaign to put the question to Montana voters. That campaign gave him the opportunity to take Tactical Civics on the road.

'It's basic civics'

Crabtree took the stage in Miles City, Montana, wearing a wired microphone headset not unlike the one Wagner was sporting in East Helena. He had prepared the presentation on Tactical Civics and the grand jury ballot initiative for Patriots Roundtable, a local group that promotes Christian conservative viewpoints on current events.

Three years after Wagner's introduction to Tactical Civics, organizers were no longer recruiting on the overreach of COVID-19 regulations now in the rearview mirror. Crabtree was talking about mainstream Montana politics, and raised Democratic U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, who then was preparing for a bruising election year.

Downtown Miles City in October.

"This is what people don't realize; that people up in Tester's county, through this, could go around in that county, collect the signatures needed to force a judge to (impanel) a grand jury, have him indicted and then try him in a criminal trial," Crabtree told the crowd from behind a large Tactical Civics logo propped up on the podium. "If he's turning a blind eye to the issue at the south border, which everyone seems to be, he's just as culpable as the people actually driving this stuff. 'We, the People' of Montana, have the power to indict our federal servants. It's a very powerful tool."

Tester ultimately lost to Republican newcomer Tim Sheehy, who was likewise hosted by Patriots Roundtable in August.

State Rep. Greg Kmetz, a self-described right-wing Republican from Custer County, heads up Patriot Roundtable, a group formed in 2022 out of hard-right Republicans' need for a stage to broadcast information not available through traditional sources. Patriots Roundtable’s first meeting included a free showing of "2,000 Mules," a documentary that traffics in false conspiracies about 2020 election.

Patriots Roundtable has matured into a political organization that outpaces the county's Republican central committee, drawing bigger crowds at their events and creating some friction between the two standard bearers of the local GOP. Mollie Phipps, president of the Custer County Republican Central Committee, said the sudden surge of Patriots Roundtable has since "resulted in some confusion and candidates being directed to the Roundtable instead of the central committee."

Kmetz said he joined Tactical Civics the day after Crabtree's presentation in Miles City, believing grand juries could be of good use to locals who are suspicious of the ballot tallies in their county. However, he did have some reservations about the low threshold signature threshold — one-half of 1% of registered voters — required to activate a grand jury.

Rep. Greg Kmetz, a self-described right-wing Republican from Custer County, heads up Patriot Roundtable, a group founded in 2022 out of hard-right Republicans’ need for a stage to broadcast information not available through traditional sources.

"I do think a percentage of registered voters needs to be high enough that it couldn't be you and me, and my buddies could call a grand jury and tip the cart over," he said.

The ballot initiative ultimately failed. Crabtree claimed to have obtained 15,000 signatures supporting the proposal for Tactical Civics' vision of citizen-led grand juries. That was well short of the 60,000 needed to put the measure on the general election ballot, but Crabtree told a crowd at a Tactical Civics event in Butte that he would take another run at it next cycle.

"I put a lot of miles on my car and spent a lot of money doing this," he told them. "But it's worth it, and we can't stop."

Wagner was among those in the crowd at that meeting in June. The group that day was small but committed — six or seven people have continued to meet every Friday morning at Perkins to read up on Tactical Civics literature.

Butte-Silver Bow County Sheriff Ed Lester said he is aware of the Tactical Civics meetings in his county and remains troubled by the group's beliefs.

"It is deeply concerning to me," he said. "They can meet and talk, that's certainly their right. … To me, the system isn't perfect but we can't have grand juries every time someone has beef with the system."

Cascade County Sheriff Jesse Slaughter.

Cascade County Sheriff Jesse Slaughter, likewise, has some hesitation about Tactical Civics' vision. Slaughter has made a name for himself as a constitutional conservative, pushing back on some mask mandates during the pandemic and supporting proposals to require federal agencies obtain permission before conducting county-level investigations.

Slaughter said he generally applauds people for engaging in civic education but was skeptical of Tactical Civics' plan for militia to carry out law enforcement duties on behalf of the grand jury.

"So now we basically just have vigilante law. That's the road we go down when we get to that point," he told the Montana State News Bureau.

Crabtree has worked to assure people that "true constitutional militia" is not the type of militia Montana has long tried to keep in the history books. He makes the point to bring up the Montana Freemen, an anti-government group that famously set up shop outside of Jordan and engaged in an 81-day standoff against federal authorities. Tactical Civics, he stated, is not the same.

"Militia is about 'We the People' taking our government back," he said in the July interview. "Why would a group of people be anti-government when the government belongs to us? It's basic civics."

Indeed, the Tactical Civics members interviewed by the Montana State News Bureau said nothing of instigating violence against public officials, although people who closely examine such groups say that Tactical Civics is an ideological descendant of the Montana Freemen.

Nick Murnion, Garfield County attorney at the time of that standoff and a target of the Freemen, is now a district court judge in that district. Asked about his thoughts between the two groups, Murnion was blunt.

"Same old stuff," he said.

Nick Murnion, Garfield County attorney at the time of that standoff and a target of the Freemen, is now a district court judge in that district.

Reporting for this series was supported in part by the Poynter Institute with funding from the Joyce Foundation. Photojournalism in this series is from Lee Newspapers' Thom Bridge and Ben Allan Smith. Montana Standard reporter Duncan Adams contributed reporting. Andy Tallman and Corbin Vanderby provided research assistance.