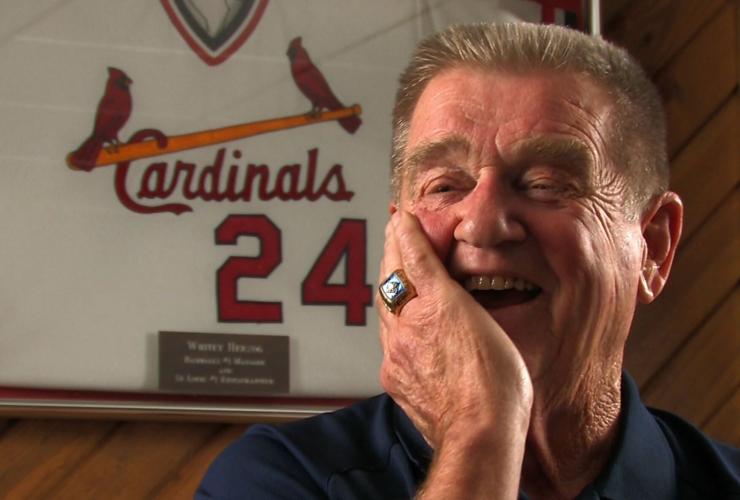

Former Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog talks with Post-Dispatch writer Rick Hummel during a December, 2009 interview at Herzog's home in Sunset Hills.

When he stepped to the microphone that stands at the peak of a career spent in baseball, Whitey Herzog first mentioned how “everybody said I was going to cry,” and he almost made it all the way through, too, without so much as a crack in his voice. Almost.

On that eventually sunny day in July 2010, a long way from where he grew up in New Athens but a short walk from where he’ll reside forever at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Herzog had a keen feel for the crowd. He always did. He sensed fans were restless after some lengthy speeches and edited his down on the fly. The Cardinals great told a tale that involved beer and getting four hits, praised the play of a rival, chided an umpire and, as if the tears were opponents, remained two steps ahead. He always was.

He didn’t waver as, from the podium, he spoke to his wife, Mary Lou Herzog, and highlighted their family seated all around her. It was only then, at the end of his speech, that he started to describe what it felt like to be inducted, to be a Hall of Famer, and the emotions started to seep between the words.

People are also reading…

“Being elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York,” Herzog said, “is like going to heaven before you die.”

An innovative and charismatic manager who had a style of baseball, “Whiteyball,” named for him, Herzog was as deft with a story as he was with a pitching change and as quick-witted as his signature teams were quick-footed.

Herzog spent this past weekend embraced by family during the final moments of an illness. He died Monday in the St. Louis area less than two weeks after he attended the Cardinals’ home opener at Busch Stadium.

He was 92.

“Whitey spent his last few days surrounded by his family,” the Herzog family said in a statement released by the club. “We have appreciated all of the prayers and support from friends who knew he was very ill. Although it is hard for us to say goodbye, his peaceful passing was a blessing for him.”

Heralded throughout his life by his peers as one of the all-time great baseball strategists, Herzog created a legacy in St. Louis that went beyond the 1982 World Series championship and three National League pennants to shape the way the Cardinals are expected to play even today. It was a style so fast, so fun to watch and so successful that the club and its fans are always chasing it. The team’s Hall of Fame is chocked with players from his teams, the club’s defensive identity and grip on earning the league’s most Gold Glove Awards began with him, and those 3 million fans expected each season — yeah, that local kid did good as Herzog helped sell all those seats and throughout the 1980s got fans leaping from them.

The style’s architect and namesake, Herzog became the crew-cut, crack-up and sometimes combative face of the franchise whose eagerness to discuss baseball strategy — sometimes with a can of Budweiser in front of him — became the model expected by Cardinals Nation of the managers who followed. His personality and availability set the table for how baseball is discussed in St. Louis to this day.

Herzog arrived here in June 1980, after a lost decade for the organization, and as longtime Post-Dispatch baseball writer Rick Hummel once said, “Cardinals baseball was changed forever.”

“I look back at Whitey Herzog as the guy who revived baseball in St. Louis,” said major league player, longtime league executive and St. Louis native Lee Thomas in 1990. “To appreciate that, you have to look back at how bad things were before he came in. He made new life in St. Louis to the tune of 3 million (fans) a year. Whitey probably had more to do with that anybody.”

“To be somewhat, if not underrated, then undercelebrated outside of Missouri,” broadcaster Bob Costas said Tuesday on MLB Network, “I think Whitey Herzog fits that description.”

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog was born in New Athens on Nov. 9, 1931. He joked during his Hall of Fame induction speech that if not for baseball he would have stayed in his working-class hometown, about 45 minutes from Busch Stadium, “digging ditches” or something. He starred in basketball and baseball and out of high school signed a contract with the New York Yankees. In 1949, he debuted with the Yankees’ Class D affiliate in McAlester, Oklahoma, where he picked up the nickname “Whitey.” He hit .279 that summer with a .361 on-base percentage and 15 stolen bases to launch a career that would include six seasons in the minors and nearly nine in the majors.

During his minor league career, Herzog would compete for attention within the Yankees organization against a young outfielder named Mickey Mantle, and in the late 1950s, Herzog would call Satchel Paige a teammate.

Herzog reached the majors in 1956 and played parts of three seasons for the Washington Senators before moving to the Kansas City Athletics, Baltimore and Detroit. He played 634 games in the majors and hit .257 with a .354 on-base percentage.

“Baseball has been good to me since I quit trying to play it,” Herzog once said.

While he never made the majors with the Yankees, he did meet his mentor there: Casey Stengel. An all-time great manager, Stengel remained an influence in Herzog’s career. He has scouted, coached and served as director of player development for the New York Mets. He was part of the group that built World Series teams in Queens for 1969 and 1973. Herzog got his first manager position in the majors with Texas in 1973. He managed the Angels in 1974 before moving to his run, from 1975 to 1979, with Kansas City. It was there, on the Royals’ home turf, that the seeds of Whiteyball began.

Hall of Famer Rick Hummel says he learned a lot from Whitey Herzog when he was manager in the 1980's. Watch as Hummel recaps covering Herzog over the years.

In 1980, the Cardinals hired Herzog as general manager and manager — the first in decades to hold both positions. He inherited a club that had not finished higher than third in the division since 1974, hadn’t finished first since 1968. He later told Hummel, a Hall of Famer himself who was a favorite chronicler and trusted confidant for Herzog, that the team “had a lot of holes, and we had a high payroll.” In December 1980, Herzog dramatically changed that.

St. Louis Cardinals president August A. Busch, Jr., left, and manager Whitey Herzog smile at the crowd that jammed downtown for a parade honoring the World Series champion baseball team on Oct. 21, 1982. In the car behind them are St. Louis County Executive Gene McNary and East St. Louis Mayor Carl Officer.

On the eve of the winter meetings, Herzog greeted Hummel at the event’s hotel in Dallas and said: “Hey, where you been? I’ve got trades to make.”

In a flurry of 23 players on the move, 14 went out, nine came in.

A year later, Herzog made his defining trade — sending a shortstop with whom he had feuded, Garry Templeton, to San Diego for the best defensive player arguably ever at the position, Ozzie Smith.

On Dec. 8, 1980, Whitey Herzog started a chain reaction of events that reshaped the Cardinals. Rick Hummel looks back at those winter meetings, when Herzog laid the foundation for a championship.

Whiteyball was full speed ahead.

The Cardinals had the best overall record in 1981, but the split-season meant no playoffs. They won the World Series in 1982 and would return there as NL champions in 1985 and 1987. In 1985, Herzog’s Cardinals, paced by Vince Coleman, stole a St. Louis-fitting 314 bases. He said he “changed the whole concept of the way to play baseball because we couldn’t hit a home run and we could neutralize the power of the other team in our ballpark.” While the steals seize the attention, Herzog’s teams ran multiple blitzes — a heavy emphasis on athletic defense, strong pitching and matchup bullpens that underscored run prevention before run prevention was cool.

Forget turf, he once told Post-Dispatch baseball writer Neal Russo that the style of play “could even win on the moon.”

In his 11 seasons with the Cardinals, Herzog’s teams won 822 games and won seven games in each of three postseason appearances. A famously missed call at first base during the 1985 World Series helped keep the Whiteyball Cardinals from a second World Series title.

“Whitey and his teams played a big part in changing the direction of the Cardinals franchise in the early 1980s with an exciting style of play,” Cardinals chairman Bill DeWitt Jr. said in a statement.

“Whitey Herzog was one of the most accomplished managers of his generation and a consistent winner with both (Interstate 70) franchises,” commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. “He made a significant impact on the St. Louis Cardinals as both a manager and general manager, with the Kansas City Royals as a manager. Whitey’s Cardinals teams reached the World Series ... by leaning on an identity of speed and defense that resonated with baseball fans across the world.”

In July 1990, Herzog abruptly resigned after a win against the Padres.

He would not return to a dugout as manager.

“You don’t replace somebody like that,” said longtime baseball executive Dave Dombrowski the day Herzog resigned. “He had a background in everything — the perfect baseball resume.”

As a manager, Herzog had two 100-win seasons, won the 1982 Major League Manager of the Year award and the 1985 NL Manager of the Year award, and ranks 39th all-time with 1,281 wins. His Hall of Fame plaque reads that he “maximized player contributions with a stern yet good-natured style, emphasizing speed, pitching and defense.”

After his career as a manager and executive, Herzog remained a presence around the Cardinals. He would annually visit spring training. He particularly liked to review the young players and offer opinions on prospects. In recent years, after a couple of falls, he had a cane handy — one made from a baseball bat engraved with his other nickname: “The White Rat.” With his fellow red jacket Cardinals Hall of Famers, he had an infectious laugh, often because he had told the story that started the laughing to begin with. During the Cardinals’ home opener earlier this month, he appeared to great ovation on the scoreboard and, during the game, talked with friends about Stan Musial.

Herzog was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the veterans committee in December 2009 and inducted that next July. Two days before he delivered that speech, before he avoided crying, he was brought to tears when, in Cooperstown, DeWitt told him of the honor that awaited him back in St. Louis.

Former Cardinals manager and 2010 Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Whitey Herzog and his wife Mary Lou wave to people they recognize along the parade route during the Parade of Legends in downtown Cooperstown, N.Y. on July 24, 2010.

The Cardinals would retire his No. 24.

“The fans loved it,” Herzog once told Hummel about the Cardinals’ play. “I still have fans every day that want to shake my hand for giving them exciting baseball for 10 years.”

Herzog is survived by his wife, Mary Lou, of 71 years; their three children, Debra, David and Jim and their spouses; nine grandchildren; and 10 great grandchildren.

The Herzog family intends to hold a private celebration of life at a later time.

The family asks any donations made as a memorial in Whitey Herzog’s name go to Shriners Hospitals for Children.

The Cardinals are planning tributes for Herzog with more details to come.

“He had a very distinctive style,” fellow Hall of Famer and Cardinals manager Tony La Russa once told Hummel. “He was involved in the game with the way he handled the bullpen and the way his offense played. Whitey’s club, both in St. Louis and Kansas City, always had those guys trying to go for doubles and triples, and that put a lot of pressure on the defense. Those guys who played for him all raved about him.

“What more do you want?”

Remembered in photos: Whitey Herzog, legendary St. Louis Cardinals manager

Whitey Herzog is shown on the video board waving to the crowd as he is introduced during pre-game ceremonies for the St. Louis Cardinals home opener versus the Miami Marlins at Busch Stadium in St. Louis on Thursday, April 4, 2024.

A plaque celebrating legendary St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog is adorned with flowers on Tuesday, April 16, 2024 in the Cardinals Hall of Fame in Ballpark Village, after the team announced his death at the age of 92.

Cardinals Hall of Fame manager Whitey Herzog waves to fans on Thursday, April 7, 2022, during ceremonies before the team’s opening day game against the Pirates at Busch Stadium. Herzog died Monday, April 15, 2024. He was 92.

Hall of Famers Lou Brock and Whitey Herzog greet players as Tony LaRussa talks with Cardinals manager Mike Shildt before playing the Milwaukee Brewers at Busch Stadium on Saturday, Aug. 18, 2018.

Former Cardinals manager and 2010 Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Whitey Herzog and his wife Mary Lou wave to people they recognize along the parade route during the Parade of Legends in downtown Cooperstown, N.Y. on July 24, 2010.

July 25, 2010 -- Former Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog gives his induction speech during the 2010 Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony at the Clark Sports Center Grounds in Cooperstown, N.Y.

Former Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog talks with Post-Dispatch writer Rick Hummel during a December, 2009 interview at Herzog's home in Sunset Hills.

Willie McGee enjoys a brief visit with his former manager, Whitey Herzog, during 1999 Cardinals spring training, including a little ribbing about why he's still out there and not retired like Whitey.

St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog sports one of his many game faces on Oct. 12, 1986.

St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog emphatically argues with home plate umpire lanny Harris in the seventh inning of a game against the Philadelphia Phillies at Busch Stadium II on Aug 5, 1983. Herzog was thrown out of the game.

St. Louis Cardinals president August A. Busch, Jr., left, and manager Whitey Herzog smile at the crowd that jammed downtown for a parade honoring the World Series champion baseball team on Oct. 21, 1982. In the car behind them are St. Louis County Executive Gene McNary and East St. Louis Mayor Carl Officer.

St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog toasts with team owner August "Gussie" Busch Jr., left, after the Cardinals won the World Series in St. Louis, on Oct. 21, 1982.

St. Louis Cardinals coach Hub Kittle, left, and manager Whitey Herzog talk about strategy during spring training in 1982.

AUGUST 26, 1981 -- Whitey Herzog pulls Cardinals shortstop Garry Templeton off the field after Templeton twice makes obscene gestures to fans who are booing him on Ladies' day. Herzog and Templeton had to be separated. Templeton later went to a treatment center.

Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog talks to his players during spring training in March 1981.

St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog during a press conference at Grant's Farm where he was named the new manager of the Cardinals photographed in June of 1980.