Luigi Nicholas Mangione, the suspect in the fatal shooting of a health care executive in New York City, apparently was living a charmed life: the grandson of a wealthy real estate developer, valedictorian of his elite Baltimore prep school and with degrees from one of the nation's top private universities.

Friends at an exclusive co-living space at the edge of touristy Waikiki in Hawaii where the 26-year-old Mangione once lived widely considered him a “great guy,” and pictures on his social media accounts show a fit, smiling, handsome young man on beaches and at parties.

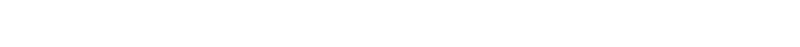

Suspect Luigi Mangione is taken into the Blair County Courthouse on Tuesday in Hollidaysburg, Pa.

Now, investigators in New York and Pennsylvania are working to piece together why Mangione may have diverged from this path to make the violent and radical decision to gun down UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in a brazen attack on a Manhattan street.

The killing sparked widespread discussions about corporate greed, unfairness in the medical insurance industry and even inspired folk-hero sentiment toward the killer.

People are also reading…

But Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro sharply refuted that perception after Mangione's arrest on Monday when a customer at a McDonald's restaurant in Pennsylvania spotted Mangione eating and noticed he resembled the shooting suspect in security-camera photos released by New York police.

Luigi Mangione, 26, appeared at an extradition hearing in connection with Thompson's Dec. 4 slaying outside a Midtown Manhattan hotel.

“In some dark corners, this killer is being hailed as a hero. Hear me on this, he is no hero,” Shapiro said. “The real hero in this story is the person who called 911 at McDonald’s this morning.”

Mangione comes from a prominent Maryland family. His grandfather, Nick Mangione, who died in 2008, was a successful real estate developer. One of his best-known projects was Turf Valley Resort, a sprawling luxury retreat and conference center outside Baltimore that he purchased in 1978.

The Mangione family also purchased Hayfields Country Club north of Baltimore in 1986. On Monday, Baltimore County police officers blocked off an entrance to the property, which public records link to Luigi Mangione’s parents. Reporters and photographers gathered outside the entrance.

The father of 10 children, Nick Mangione prepared his five sons — including Luigi Mangione’s father, Louis Mangione — to help manage the family business, according to a 2003 Washington Post report. Nick Mangione had 37 grandchildren, including Luigi, according to the grandfather's obituary.

Luigi Mangione’s grandparents donated to charities through the Mangione Family Foundation, according to a statement from Loyola University commemorating Nick Mangione’s wife’s death in 2023. They donated to various causes, including Catholic organizations, colleges and the arts.

One of Luigi Mangione’s cousins is Republican Maryland state legislator Nino Mangione, a spokesman for the lawmaker’s office confirmed.

“Our family is shocked and devastated by Luigi’s arrest,” Mangione’s family said in a statement posted on social media by Nino Mangione. “We offer our prayers to the family of Brian Thompson and we ask people to pray for all involved.”

Mangione, who was valedictorian of his elite Maryland prep school, earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in computer science in 2020 from the University of Pennsylvania, a university spokesman told The Associated Press.

He learned to code in high school and helped start a club at Penn for people interested in gaming and game design, according to a 2018 story in Penn Today, a campus publication.

His social media posts suggest he belonged to the fraternity Phi Kappa Psi. They also show him taking part in a 2019 program at Stanford University, and in photos with family and friends at the Jersey Shore and in Hawaii, San Diego, Puerto Rico and other places.

The Gilman School, from which Mangione graduated in 2016, is one of Baltimore’s elite prep schools. The children of some of the city’s wealthiest and most prominent residents, including Orioles legend Cal Ripken Jr., have attended the school. Its alumni include sportswriter Frank Deford and former Arizona Gov. Fife Symington.

This video image shows Luigi Mangione, a suspect in the fatal shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, at a McDonald's on Monday in Altoona, Pa.

In his valedictory speech, Luigi Mangione described his classmates’ “incredible courage to explore the unknown and try new things.”

Mangione took a software programming internship after high school at Maryland-based video game studio Firaxis, where he fixed bugs on the hit strategy game Civilization 6, according to a LinkedIn profile. Firaxis' parent company, Take-Two Interactive, said it would not comment on former employees.

He more recently worked at the car-buying website TrueCar, but has not worked there since 2023, the head of the Santa Monica, California-based company confirmed to the AP.

From January to June 2022, Mangione lived at Surfbreak, a “co-living” space at the edge of touristy Waikiki in Honolulu.

Like other residents of the shared penthouse catering to remote workers, Mangione underwent a background check, said Josiah Ryan, a spokesperson for owner and founder R.J. Martin.

“Luigi was just widely considered to be a great guy. There were no complaints,” Ryan said. “There was no sign that might point to these alleged crimes they’re saying he committed.”

At Surfbreak, Martin learned Mangione had severe back pain from childhood that interfered with many aspects of his life, including surfing, Ryan said.

“He went surfing with R.J. once but it didn’t work out because of his back,” Ryan said, but noted that Mangione and Martin often went together to a rock-climbing gym.

Mangione left Surfbreak to get surgery on the mainland, Ryan said, then later returned to Honolulu and rented an apartment. An image posted to a social media account linked to Mangione showed what appeared to be an X-ray of a metal rod and multiple screws inserted into someone's lower spine.

Martin stopped hearing from Mangione six months to a year ago.

Mangione likely was motivated by his anger at what he called “parasitic” health insurance companies and a disdain for corporate greed, according to a law enforcement bulletin obtained by AP.

He appeared to view the targeted killing of the UnitedHealthcare CEO as a symbolic takedown, asserting in his note that he is the “first to face it with such brutal honesty,” the bulletin said.

Healthcare history: How U.S. health coverage got this bad

Healthcare history: How U.S. health coverage got this bad

Key Points

- Health care in America has evolved in some ways, but in others, it continues to be a complex and arduous process for employees and employers alike.

- The Affordable Care Act, or ACA, made it a legal requirement for Americans to have a health insurance plan, regardless of employment status.

- ACA opened the door for health care expansion, including the marketplace, HRAs, and more.

In the U.S. healthcare system, even the simplest act, like booking an appointment with your primary care physician, may feel intimidating. As you wade through intake forms and insurance statements, and research out-of-network coverage, you might wonder, "When did U.S. health care get so confusing?"

Short answer? It's complicated. The history of modern U.S. health care spans nearly a century, with social movements, legislation, and politics driving change.

Take a trip back in time as Thatch highlights some of the most impactful legislation and policies that gave us the existing healthcare system, particularly how and when things got complicated.

History of U.S. Health Care

- 1930s: Great Depression and the birth of health plans that primarily covered the cost of hospital stays.

- 1942: Creation of employer-sponsored health care in the wake of wage freezes.

- 1965: Medicare and Medicaid debut.

- 1986: COBRA is signed, offering former employees the opportunity to stay on employer health care.

- 2010: Affordable Care Act signed into law.

- 2019: ICHRAs introduced.

Past Is Prologue

In the beginning, a common perception of American doctors was that they were kindly old men stepping right out of a Saturday Evening Post cover illustration to make house calls. If their patients couldn't afford their fee, they'd accept payment in chicken or goats. Health care was relatively affordable and accessible.

Then it all fell apart during the Great Depression of the 1930s. That's when hospital administrators started looking for ways to guarantee payment. According to the American College of Healthcare Executives, this is when the earliest form of health insurance was born. Interestingly, doctors would have none of it at first. The earliest health plans covered hospitalization only.

A new set of challenges from the Second World War required a new set of responses. During the Depression, there were far too many people and too few jobs. The war economy had the opposite effect. Suddenly, all able-bodied men were in the military, but somebody still had to build the weapons and provision the troops. Even with women entering the workforce in unprecedented numbers, there was simply too much to get done. The competition for skilled labor was brutal.

A wage freeze starting in 1942 forced employers to find other means of recruiting and retaining workers. Building on the recently mandated workers' compensation plans, employers or their union counterparts started offering insurance to cover hospital and doctor visits.

Of course, the wage freeze ended soon after the war. However, the tax code and the courts soon clarified that employer-sponsored health insurance was non-taxable.

The Start of Medicare and Medicaid

Medicare, a government-sponsored health plan for retirees 65 and older, debuted in 1965. Nowadays, Medicare is offered in Parts A, B, C, and D; each offering a different layer of coverage for older Americans. As of 2023, over a quarter of all U.S. adults are enrolled in Medicare.

The structure of Medicare is not dissimilar to universal health care offered in other countries, although the policy covers everyone, not just people over a certain age.

Medicaid was also signed into law with Medicare. Medicaid provides health care coverage for Americans with low incomes. Over 74 million Americans are enrolled in Medicaid today.

Nixoncare?

The Obama administration was neither the first nor the last to champion new ways to provide health care coverage to a wider swath of Americans.

The first attempts to harmonize U.S. healthcare delivery systems with those of other developed economies came just five years after Medicare and Medicaid. Two separate bills were introduced in 1970 alone. Both bills aimed to widen affordable health benefits for Americans, either by making people Medicare-eligible or providing free health benefits for all Americans. As is the case with many bills, both these died, even though there was bipartisan support.

But the chairman of the relevant Senate panel had his own bill in mind, which got through the committee. It effectively said that all Americans were entitled to the kind of health benefits enjoyed by the United Auto Workers Union or AFL-CIO—for free. But shortly after Sen. Edward Kennedy began hearings on his bill in early 1971, a competing proposal came from an unexpected source: Richard Nixon's White House.

President Nixon's approach, in retrospect, had some commonalities with what Obamacare turned out to be. There was the employer mandate, for example, and an expansion of Medicaid. It favored healthcare delivery via health maintenance organizations, or HMOs, which was a novel idea at the time. HMOs, which offer managed care within a tight network of health care providers, descended from the prepaid health plans that flourished briefly in the 1910s and 1920s. They were first conceived in their current form around 1970 by Dr. Paul M. Ellwood, Jr. In 1973, a law was passed to require large companies to give their employees an HMO option as well as a traditional health insurance option.

But that was always intended to be ancillary to Nixon's more ambitious proposal, which got even closer to what exists now after it wallowed in the swamp for a while. When Nixon reintroduced the proposal in 1974, it featured state-run health insurance plans as a substitute for Medicaid—not a far cry from the tax credit-fueled state-run exchanges of today.

Of course, Nixon had other things to worry about in 1974: inflation, recession, a nation just beginning to heal from its first lost war—and his looming impeachment. His successor, Gerald Ford, tried to keep the proposal moving forward, but to no avail.

But this raises a good question: If the Republican president and the Democratic Senate majority both see the same problem and have competing but not irreconcilable proposals to address it, why wasn't there some kind of compromise? What major issue divided the two parties?

It was a matter of funding. The Democrats wanted to pay for universal health coverage through the U.S. Treasury's general fund, acknowledging that Congress would have to raise taxes to pay for it. The Republicans wanted it to pay for itself by charging participants insurance premiums, which would be, in effect, a new tax.

The Birth of COBRA Coverage

The next significant legislation came from President Reagan, who signed the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, or COBRA, in 1985. COBRA enabled laid-off workers to hold onto their health insurance—providing that they pay 100% of the premium, which had been wholly or at least in part subsidized by their erstwhile employer. While COBRA offers continued coverage, its high expense doesn't offer much relief for the unemployed. A 2006 Commonwealth Fund survey found that only 9% of people eligible for COBRA coverage actually signed up for it.

The COBRA law had a section, though, that was only tangentially related. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act, or EMTALA, which was incorporated into COBRA, required all emergency medical facilities that take Medicare—that is, all of them—to treat patients irrespective of their insurance status or ability to pay. As Forbes staff writer Avik Roy wrote during the Obamacare debate, EMTALA has come to overshadow the rest of the COBRA law in its influence on American health care policy. More on that soon.

The Clinton Debacle

It wasn't until the 1990s that Washington saw another serious attempt at healthcare reform. Bill Clinton's first order of business as president was to establish a new health care plan.

For the first time, the First Lady took on the role of heavy-lifting policy advisor to the president and became the White House point person on universal health care. Hillary Clinton's proposal mandated:

- Everyone enrolls in a health coverage plan.

- Subsidies would be provided to those who can't afford it.

- Companies with 5,000 or more employees would have to provide such coverage.

The Clintons' plan centralized decision-making in Washington, with a "National Health Board" overseeing quality assurance, training physicians, guaranteeing abortion coverage, and running both long-term care facilities and rural health systems.

The insurance lobbyists had a field day with that. The famous "Harry and Louise" ads portrayed a generic American couple having tense conversations in their breakfast nook about how the federal government would come between them and their doctor. By the 1994 midterms, any chance of universal health care in America had died.

In this case, it wasn't funding but the debate between big and small governments that killed the Clinton reform. It would be another generation before the U.S. saw universal health care take the stage.

The Birth of Obamacare

Fast-forward to 2010. It was clear that employer-sponsored plans were vestiges of another time. They made sense when people stayed with the same company for their entire careers, but as job-hopping and layoffs became more prevalent, plans tied to the job became obsolete.

Thus the Affordable Care Act, or ACA, was proposed by Barack Obama's White House and squeaked by Congress and the Supreme Court with the narrowest of margins.

The ACA introduced an individual mandate requiring everyone to have health insurance regardless of job status. It set up an array of government-sponsored online exchanges where individuals could buy coverage. It also provided advance premium tax credits to defray the cost to consumers.

But it didn't ignore hat most people were already getting health insurance through work, and a significant proportion didn't want to change. So the ACA also required employers with 50 or more full-time equivalent employees to provide health coverage to at least 95% of them. The law, nicknamed Obamacare by supporters and detractors, set a minimum baseline of coverage and affordability. The penalty for an employer that offers inadequate or unaffordable coverage can never be greater than the penalty for not offering coverage at all.

The model for Obamacare was the health care reform package that went into effect in Massachusetts in 2006. The initial proposal was made by then-Governor Mitt Romney, a Republican who now serves as a senator from Utah.

What Came Next

Despite an onslaught of court challenges, Obamacare remains the law of the land. For a while, Republican congressional candidates ran on a "repeal-and-replace" platform plank, but even when they were in the majority, there was little legislative action to do either.

Still, Obamacare is not the last word in American health care reform.

Since then, there have been two important improvements to Health Reimbursement Arrangements, through which companies pay employees back for out-of-pocket medical-related expenses. HRAs had been evolving informally since at least the 1960s but were first addressed by the Internal Revenue Service in 2002.

Not much more happened on that front until Obama's lame-duck period. In December 2016, he signed the bipartisan 21st Century Cures Act, which was mainly a funding bill supporting the National Institutes of Health as it addressed the opioid crisis.

But, just like the right to free emergency room treatment was nested in the larger COBRA law, the legal framework of Qualified Small Employer Health Reimbursement Arrangements was tucked away in a corner of the Cures Act.

QSEHRAs, offered only by companies with fewer than 50 full-time employees, allow firms to let their employees pick their insurance coverage off the Obamacare exchanges. The firms pay the employees back for some or all of the cost of those premiums. The employees then become ineligible for the premium tax credit provided by the ACA, but a well-constructed QSEHRA will meet or exceed the value of that subsidy.

That brings this timeline to one last innovation, which expands QSEHRA-like treatment to companies with more than 50 employees or aspiring to have them.

Introducing ICHRAs

Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangements, or ICHRAs, were established by a 2019 IRS rule.

ICHRAs allow firms of any size to offer employees tax-free contributions to cover up to 100% of their individual health insurance premiums as well as other eligible medical expenses.

Instead of offering insurance policies directly, companies advise employees to shop on a government-sponsored exchange and select the best plan that suits their needs. Employer reimbursement rather than an advance premium tax credit reduces premiums. And because these plans are already ACA-compliant, there's no risk to the employer that they won't meet coverage or affordability standards.

The U.S. is never going back to the mid-20th century model of lifetime employment at one company. Now, with remote employees and gig workers characterizing the workforce, the portability of an ICHRA provides some consistency for those who expect to be independent contractors for their entire careers. Simultaneously, allows bootstrap-phase startups to offer the dignity of health coverage to their Day One associates.

How We Got Here, Where We're Headed—A Fairer, Kinder Health Care System

The U.S. health care system can feel clunky and confusing to navigate. It is also regressive and penalizes startups and small businesses. For a country founded by entrepreneurs, it's sad that corporations like Google pay less for health care per employee than a small coffee shop in Florida.

In many ways, ICHRA democratizes procuring health care coverage. In the same way that large employers enjoy the benefits of better rates, ICHRA plan quality and prices improve as the ICHRA risk pool grows. Moving away from the traditional employer model will change the incentive structure of the healthcare industry. Insurers will be able to compete and differentiate on the merits of their product. They will be incentivized to build products for people, not one-size-fits-all solutions for employers.

This story was produced by Thatch and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.