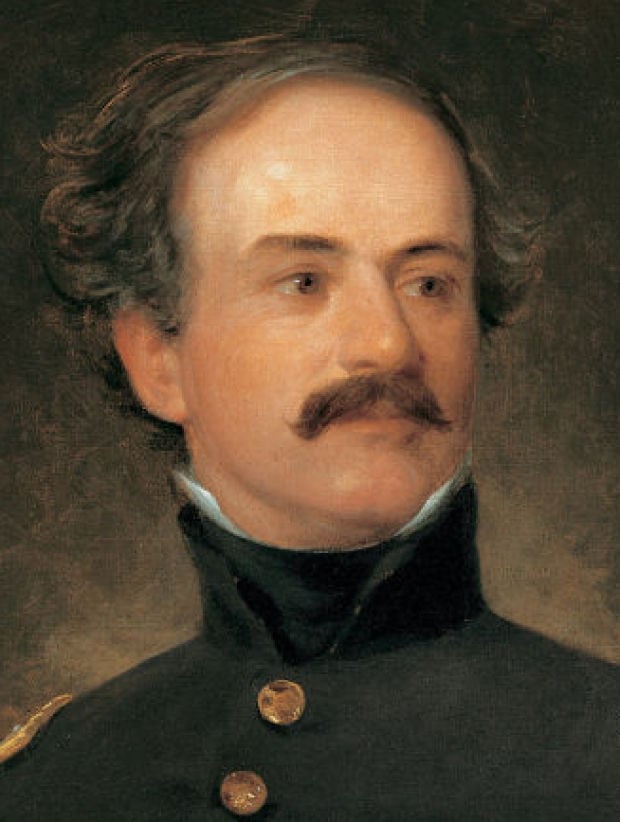

Bloody Island, a sandbar in the Mississippi River, was a popular site for deadly duels in the 19th century.

ST. LOUIS • “I can forgive you. I do forgive you.”

Those were the last recorded words of Charles Lucas, 25, felled by a single pistol shot from rival lawyer Thomas Hart Benton. The duel took place Sept. 27, 1817, on Bloody Island in the Mississippi River across from St. Louis.

Their meeting is the most infamous duel here because Benton later became a national figure, serving Missouri in the U.S. Senate for 30 years. Matters of petty ego led them to the island. But their rivalry was shaped by the opposite sides they took in St. Louis’ first major political schism — the prolonged fight over land titles between the French-speaking founding families and the American newcomers.

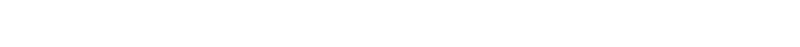

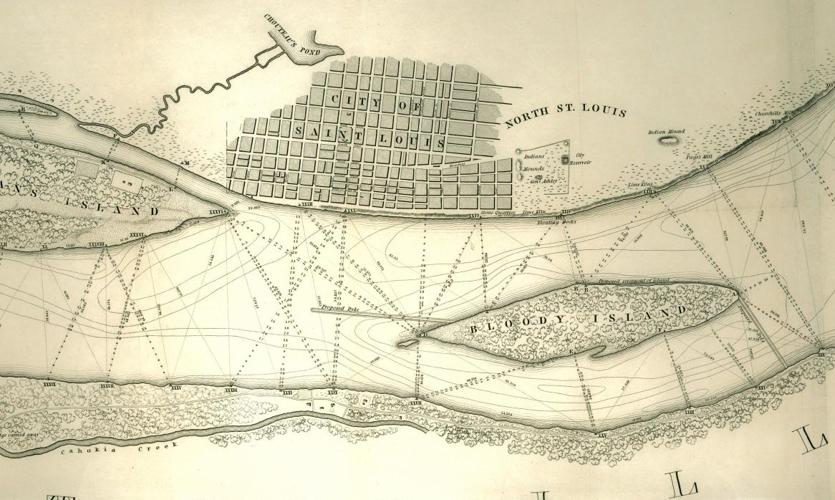

Thomas Hart Benton (left) and Charles Lucas clashed in a fatal duel on Bloody Island on Sept. 27, 1817.

Lucas was a son of Judge Jean Baptiste Charles Lucas, a former congressman from Pittsburgh. In 1805, President Thomas Jefferson appointed the elder Lucas to the Board of Land Commissioners for the Territory of (upper) Louisiana. Despite Lucas’ French birth, he fiercely opposed many of the holdings of the Chouteau family and its allies, to whom the former Spanish colonial rulers had bestowed generous grants.

People are also reading…

Many newcomers thought the Louisiana Purchase made the land America’s to dispense. Further complicating things were the difficulties of making detailed surveys in a wilderness and the hurried nature of some Spanish grants, especially those written near the end of colonial days.

Benton arrived here in 1815 from Tennessee after tangling with future president Andrew Jackson. Benton quickly made friends with Charles Gratiot, a brother-in-law of first citizen Auguste Chouteau. Benton took the founders’ side in the land fight.

In a routine court case in 1816, Benton and Charles Lucas traded insults during closing arguments. On election day in August 1817, Lucas publicly questioned Benton’s right to vote. Incensed, Benton said, “I do not propose to answer charges made by any puppy who may happen to cross my path.”

Lucas challenged him to a duel. They met 12 days later on the island and wounded each other. Residual hard feelings led six weeks later to the fatal replay.

Benton became a newspaper editor and added statehood for Missouri to his passions. Elected U.S. senator by the legislature, he began shifting his sympathies to the growing number of farmers and other small landholders. In 1824, he proposed less-desirable land be given free to poor families if they would work it.

The larger land disputes lingered for decades in the courts, the last one settled by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1888. Resolutions defy easy summary. The commissioners generally upheld even shaky land claims if they were small and owner-occupied. The founding families survived well enough — Auguste Chouteau still held more than 50,000 acres when he died in 1829.

In the end, both sides could claim vindication. J.B.C. Lucas ended his days scorning Benton as an assassin and tending to extensive family land holdings, including a large tract northwest of St. Louis his late son called Normandy. The name endures as a suburb and school district.

An 1837 map of St. Louis and the Mississippi River showing Bloody Island, which had begun as a sand bar about the year 1800. It was attractive to duelists because it was not clearly Missouri or Illinois territory. The Benton-Lucas duel was one of several on the island by prominent St. Louisans. Because the presence of the island threatened to push the Mississippi River channel away from the St. Louis steamboat landing, Army engineer Robert E. Lee helped build a barrier that restored the western channel and eventually fused Bloody Island with the Illinois riverbank. Missouri History Museum image

Other prominent duels at Bloody Island

Here are two other duels that took place on Bloody Island between prominent St. Louisans:

• On June 30, 1823, Thomas Rector shot and killed Joshua Barton, who was U.S. attorney here and a U.S. senator's brother. Barton was the source of an anonymous newspaper article that accused Rector's brother, federal surveyor William Rector, of padding his payroll. William Rector was away from town, so his brother, Thomas, demanded the duel to protect family honor. The distance was 10 paces. Rector was unharmed.

• On Aug. 26, 1831, U.S. Rep. Spencer Pettis and retired army Maj. Thomas Biddle both died in a point-blank exchange of pistol shots. Pettis had criticized the Bank of the United States, which was run by Biddle's brother, Nicholas, and a major flashpoint in Jacksonian-era politics. After Thomas Biddle assaulted Pettis in a hotel, Pettis issued a challenge to duel. That meant Biddle could set the terms. He chose face-to-face because he was nearsighted.

Despite laws against dueling, old-time honor sometimes still demanded gunfire. On Aug. 26, 1856, U.S. Attorney Thomas Reynolds wounded newspaper editor Gratz Brown on an island near Herculaneum, a secret location they chose because police were watching Bloody Island. Theirs was the last local duel to draw blood.

Tim O'Neil is a reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Contact him at 314-340-8132 or toneil@post-dispatch.com