St. Louis University professor Sarah Adam competes for the United States in a wheelchair rugby game.

Putting herself in a wheelchair was not part of Sarah Adam’s role as a volunteer for a St. Louis quad rugby club during her years studying occupational therapy at Washington University.

She helped with various tasks after her introduction to the sport in 2013 by associate professor Kerri Morgan, who had played internationally for the U.S.

Adam fell in love with the sport and the community of players. She considered other ways to contribute beyond filling in when there was a shortage of players. Maybe as a coach or referee.

“We had a group of students helping and they all loved it, but Sarah loved it in a different way,” Morgan said. “You could see her competitive spirit. It was a challenge to her.”

In the years that followed, the challenge grew significantly for someone who had spent her life playing sports.

People are also reading…

Adam was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2016, around the time she was preparing to graduate. By 2020, she was using a wheelchair full time.

Now, Adam, a St. Louis University assistant professor of occupational therapy, has become the first woman to make the U.S. wheelchair rugby team for the Paralympics. She and the team will compete in Paris this summer.

Adam will participate at the highest level in a sport she first heard about during a lecture by Morgan, whose lab she eventually joined as an undergraduate. It was a fortuitous sequence of events, including choosing Washington University, that Adam does not believe occurred by chance.

“I frequently reflect on how many things had to fall into place at the right time to get me to where I am today,” she said. “Being in St. Louis connected me with a group of like-minded, athletic, independent, determined individuals who didn’t let their disability be an excuse. Too many things have happened in the right way at the right time for me to think it’s just coincidence.”

The student turned professor and her former mentor remain close friends, and sometimes teammates, in a bond formed through the common interest in occupational therapy and fortified by physical conditions.

The depth of that connection could not have been anticipated before Adam’s diagnosis, when they worked together on a paper addressing community-based exercise programs for people with disabilities.

“It’s pretty wild,” Morgan said. “Sometimes things just work out right. She got a really crappy diagnosis and was in a good place to be supported and excel at something she’s been good at in her life, which was sports.”

Adam is a significant piece of the U.S. team that won a gold medal last November at the Parapan American Games in Santiago, Chile. Next, she will extend the path started by Morgan in 2007, when she was the first woman on the U.S. team, although she never reached the Paralympics.

“My whole future was planned out, and suddenly there was so much uncertainty,” Adam said. “I credit my athletic background to taking the ‘next play’ mentality. Being connected with the disability community, I came out the other end even better. My life is phenomenal right now.”

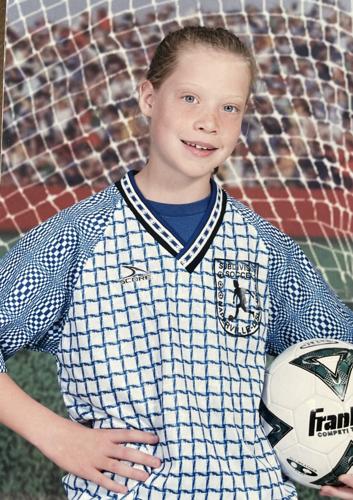

Sarah Adam played youth soccer and softball growing up before her diagnosis with multiple sclerosis.

‘She’s an amazing player’

Adam, who grew up in Naperville, Illinois, had an active childhood in sports, including softball and soccer. She played one year of Division III college softball. But there were early signs of what was to come.

Doctors told her the MS could have had its origin when she was as young as 9. She experienced numbness in her hands in high school. More difficulties followed, and a professor at Washington University suggested she get it checked.

Adam was treated for nine months before neurological symptoms emerged. It took another 18 months for the final diagnosis. Adam found her mobility getting worse and her legs “flailing” as it became harder to move her feet. By this time, Morgan, who became a Paralympic track athlete, had gone to Alabama for a post-doctoral fellowship.

“When I came back from that, she told me,” Morgan said. “She was struggling with some things, so I can’t say it totally surprised me. ... She took advantage of it. She’s an amazing player who elevated to the top level.”

Adam helped players into wheelchairs among other responsibilities during college, and now she has her own, including the $10,000 custom-made version used in competition.

She played her first event in 2019 but was unsure if her level of impairment was enough to allow her to compete. The sport requires medical professionals to evaluate the functional ability of prospective players to determine if they qualify.

Sarah Adam helped lead the United States to a gold medal at the Parapan Games in Santiago, Chile.

“I have so much respect for the sport,” Adam said. “I was borderline and didn’t want to class in if I didn’t belong. There was a lot of debate. It was a difficult decision, but I had so much support from my teammates.”

Adam was invited to the U.S. team tryouts with about 40 other athletes; 12 eventually would be chosen for the Paralympics. Also on the team is Eric Newby, who attended Nashville (Illinois) High and Maryville University.

“I thought there was absolutely no way I’d make the team,” she said. “It was cool to be invited to see how I stacked with the best in the world. Having an athletic mentality and growing up playing sports with my brother and older guys, it never bothered me to compete a little outside of my comfort zone.”

Adam attended training sessions in Birmingham, Alabama, several times and now is training on her own before going to Paris. She works with a personal trainer and by herself. Part of her regimen is conditioning work on some of the “gnarly hills” in Forest Park, including the uphill trail running south along Skinker Boulevard.

Wheelchair rugby is a high contact sport, and Adam often finds her chair and 140-pound body colliding with opposing 200-pounders. When she takes a tumble, she has trained herself to give a thumbs-up sign for her mother to see.

The sport includes a classification system for each athlete based on the level of functionality, from 0.5 to 3.5, with higher numbers indicating more function. Adam is a 2.5 but considered a 2.0 in international play because she is a woman. Teams use four players at a time and the combined classification can be no more than 8.0.

Adam hopes to avoid any setbacks before the Paralympics, which run Aug. 28 to Sept. 8. Overwork and stress can exacerbate symptoms of her MS, including fatigue. The overwork part can be tough because she has become a vital player and was on the court nearly the entire game when the U.S. won in Chile.

She has persevered because she is not only playing for herself and the country but for others in her situation.

“They need someone to look up to who plays sports,” she said. “For me, it was a nice way to break down stereotypes of what it means to be a person with a disability with MS, and to show my body can do amazing things and doesn’t need to be put in a bubble.”